A Method For Dropping Perfectionism

Perfectionism is by no means a roadblock that exclusively affects musicians, but the toll it can take on our growth can be so paralyzing that many of us choose to either procrastinate our practice or give up the craft altogether. I empathize with the feeling of staring at or listening to unfamiliar material and experiencing thoughts like, “There’s no way I could ever play something like that,” or, one of the ego’s favorites, “they must just have something I don’t!” Both of these are lies we tell ourselves out of fear of imagined failure. By narrowing the scope of our practice and prioritizing a state of calm, we can master any specific piece of music, style, technique, or instrument.

Shortly after graduating from Bard College, I found myself trapped in unproductive thought patterns that could best be summarized as, “You are not a good enough musician. There is so much musical material you’re still unfamiliar with and you’ll never manage to get to all of it. Why bother?” As you can probably tell this mindset wasn’t exactly conducive to putting in the necessary work each day to see incremental results. Even if I had achieved those results, my ego still wouldn’t have been satisfied. This disconnection led me to discovering the teachings of Kenny Werner outlined in his spiritual, as well as practical book for musicians, Effortless Mastery. While I may not believe in everything he writes in the way he writes it, Kenny’s wisdom opened my eyes to several big-picture realizations that helped me nurture, cherish, and share my talent despite my shortcomings.

The first mind pattern we can work to dissolve is that of “not being a good musician.” I ask you to think of some of your favorite pieces of music of all time. Is every single one of them impossibly complicated and virtuosic; requiring incredible technical ability? Next, think of some artists that have moved you. Could you play any of their music yourself? -Could your children? Is it all impossibly difficult? Do they ever make mistakes when performing live? Would you refer to them as not being a good musician if any of these answers are yes? Do mistakes even make music less beautiful? Is there such thing as a mistake? The truth is that there really is no difference between you and your favorite artist. Yes, there may be musical material that they have familiarized themselves with before you, but all of that is icing on the cake. There is nothing you can learn that will legitimize your playing. You are a legitimate musician already; no matter what instrument you play, how you play it or how long you’ve been playing it. You can work towards refining your craft and learning new material to more accurately paint the picture while knowing the subject remains the same. In fact, you may find that once you drop the need to improve, you are able to improve more quickly and painlessly because the action of learning becomes enjoyable! So while the answer to the question “Why Bother?”, is a nuanced and ever-evolving one that will vary from person to person, I know that joy is a fairly reliable North Star.

You can work towards refining your craft and learning new material to more accurately paint the picture while knowing the subjects remains the same

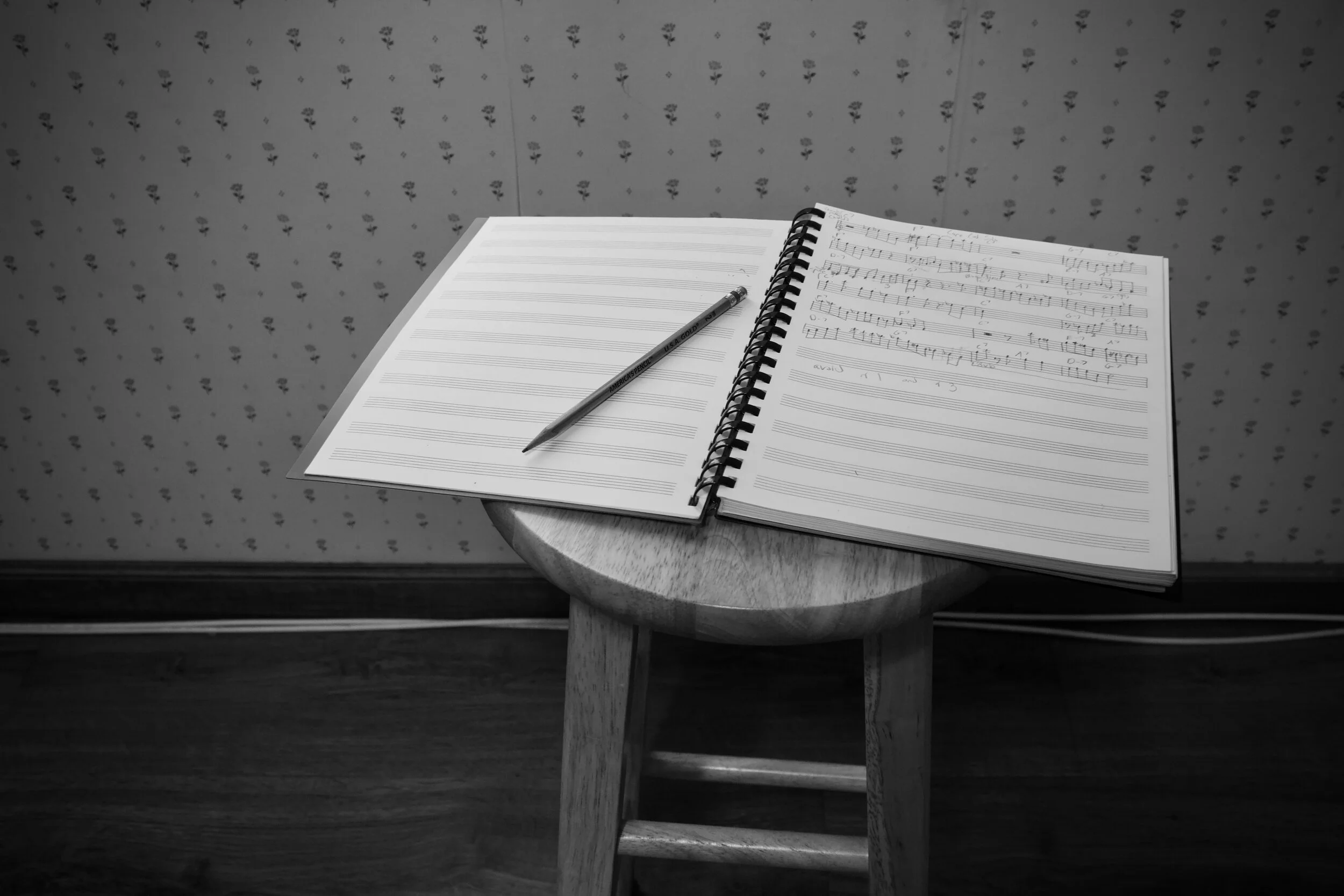

Now let’s address the mind pattern, “There is so much musical material you’re still unfamiliar with and you’ll never manage to get to all of it.” The statement itself is objectively true. There is an infinite amount of musical information out there and you will never get to all of it, but as we discussed earlier, there is no need to get to all of it. Now what about the material we want to learn? Regardless of whether the material is learning new scales, techniques, transcriptions or repertoire, I’ve come to rely on a simplified triangle method that’s heavily inspired by Kenny Werner’s learning diamond.

The idea is that we can’t hear or look at an unfamiliar musical information and immediately execute it calmly, correctly, and at tempo. Instead, we pick two, or even one of these to work on at a time. Part of the joy that music brings comes from the calm that comes over our minds as we play and create, so we definitely want to prioritize that over the other two. For instance, if you’re learning a Charlie Parker solo, attempting to play it for the first time correctly and at tempo may make you feel anything but calm. Drop the expectation of getting it all right and either calmly play through it as slowly as you need to, or calmly play it faster while ignoring any mistakes. If you find yourself losing calm while trying to play correctly you are playing too fast, and if you find yourself losing calm while playing faster you are too concerned with playing correctly. You may also consider applying this method to isolated sections of the material that are giving you the most trouble. I’ve found tackling practice in this way to be the quickest way to digest new material. Once you’re able to play the material calmly, correctly and at tempo, the unfamiliar has become familiar. The word calm in this method can also be replaced with “effortlessly” or “without thinking.”

Once you’re able to play the material calmly, correctly and at tempo, the unfamiliar has become familiar

Perfectionism can be an insidious hindrance to any musician, but by narrowing the scope of our practice, prioritizing joy and reminding ourselves of the inherent value of every note we play or sing, we can banish it from the practice room and meet every one of our goals - calmly but surely.